An Art of Choice: Composing Paragraphs (Part 3)

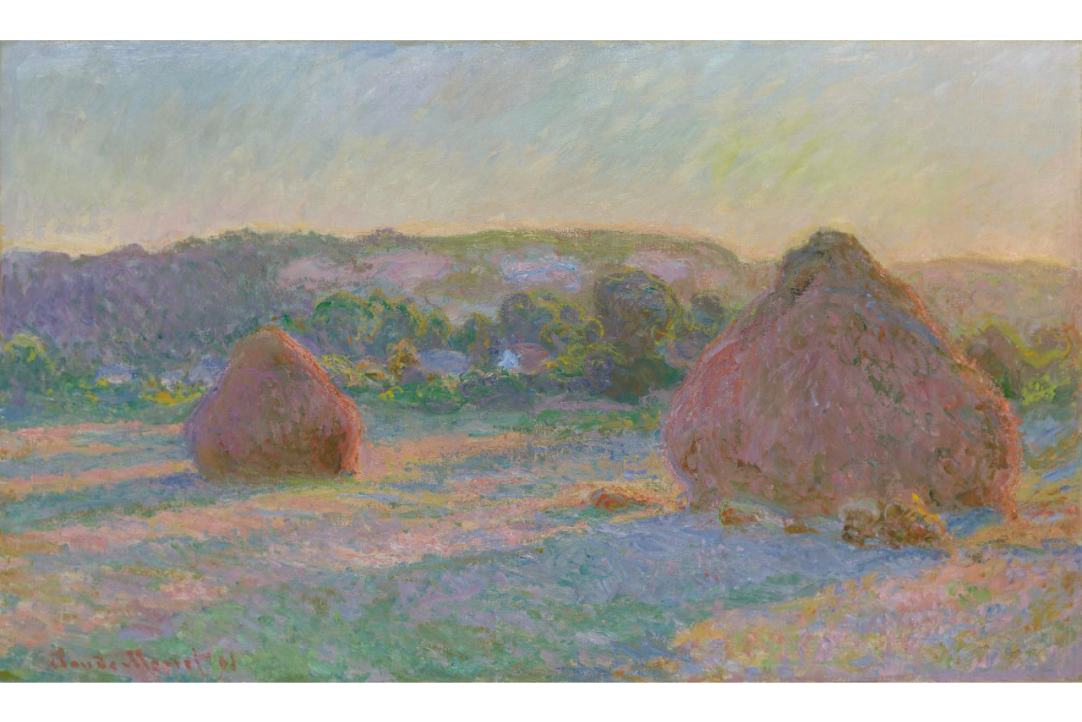

Claude Monet, Stack of Wheat, (Thaw, Sunset), Oil on Canvas, 1891, Art Institute of Chicago

By Dr. Melvin Hall,

Ph.D. in Composition and Rhetoric

from the University of Wisconsin — Madison.

❞ The Beautiful is the appropriate.

How Do Writers Know When a Paragraph is Complete?

How Do Writers Revise Their Writing to Learn the Appropriate?

How Do Genre and Audience Shape a Paragraph’s Form?

Nuno, F. R. et al. (2021, 14 April). Genomics and epidemiology of the P.1 SARS-CoV-2 lineage in Manaus, Brazil. Science, 327(6544), pp. 815-821.

The takeaway is that a paragraph’s genre and readers’ expectations affect a writer’s and readers’ sense of what is appropriate for a paragraph’s shape and size. So if I am writing for a newspaper (and its readers), I will have to divide the twelve-sentence paragraph that we drafted in Part 2 into several paragraphs of between one and two sentences. If I am writing an academic or literary article (scholarly readers), I can probably leave the paragraph at twelve sentences. However, writers will have to carefully study the articles published in their target journals. For example, as I scan a feature article in the journal Nature, a leading international scientific journal, I discover the paragraphs are between one and two sentences long – occasionally three and four sentences (Lenharo, 2024, pp. 438 – 40). Yet, in articles dedicated to reporting scientific research, paragraphs can be quite long: ten to twelve sentences. (Nuno, 2021, pp. 815 – 821).