An Art of Choice: Composing Paragraphs (Part 2)

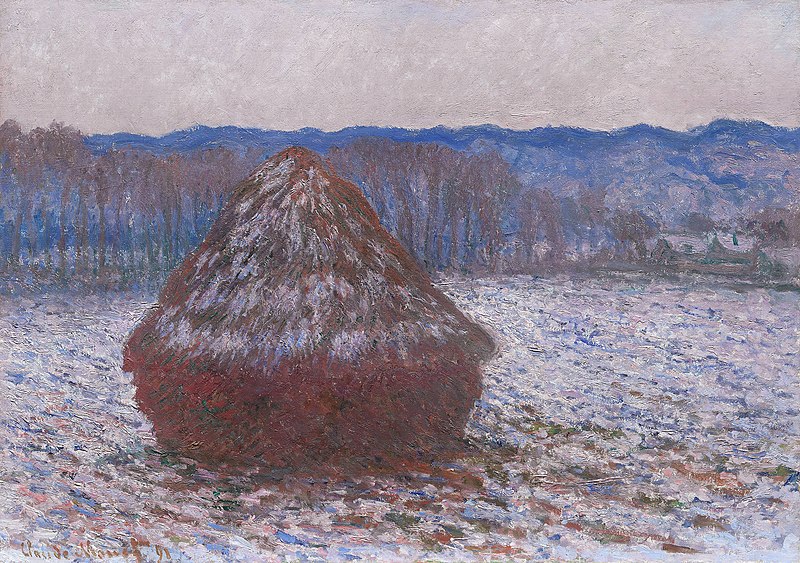

Claude Monet, Stack of Wheat, (Thaw, Sunset), Oil on Canvas, 1891, Art Institute of Chicago

By Dr. Melvin Hall,

Ph.D. in Composition and Rhetoric

from the University of Wisconsin — Madison.

❞ Form always makes one tacit statement – it says: I am a definite form of existence; I choose to have character and quality; I choose to be recognizable; I am – everything considered – the best that could be done under the circumstances, and so superior to a blob.

- Norman Mailer, Cannibals and Christians

How Do Paragraphs Move from Blob to Form?

In Part 1, reading, observing, and listing afforded us with the conceptual material needed to shape a paragraph.

Some writers would skip listing and simply begin writing. Using the paragraph as a tool to simultaneously afford and organize their ideas. This is sometimes referred to as “free writing.” Whether a writer creates a physical list or just begins writing, the list still represents the initial stage of a writer’s thinking and writing process – a snapshot of what is going on in the writer’s mind. Writers begin with afforded material and chaos (in their mind or on paper), what Mailer in the blog’s epigraph calls a blob. Our aim in this blog is to show how writers make choices to move from blob to form to compose a paragraph of coherent meaning. We will watch the list from Part 1 metamorphose into a paragraph.

Common Places (Topics)

Common places (sometimes referred to as topics or topoi) are very helpful heuristic tools; they help order and arrange ideas. They have a lot in common with generative opposites. Scholars of rhetoric and argument have collected and documented the basic common places for over 2,000 years. Quintilian describes common places as the mental “areas in which Arguments lurk and from which they have to be drawn out.”(Quintilian, 5.10)

As with all heuristic devices, there is an element of trial and error involved. Table 1 lists the basic common places and logic that help writers organize their thought and draft paragraphs. Because we are writing a paragraph that answers the question What is the science fiction genre of film? it is easy for us to choose the common place definition to draft our paragraph.

Here is the basic structure of the common place definition. Its three parts are color coded for reference:

Generative Opposites

Generative opposites are cognitive dynamos that impel thought. If we think of the mind as being in motion, generative opposites set the mind in motion and orient its trajectory. Like the moon setting the tides in motion, generative opposites set thought moving to-and-fro, back-and-forth. They transform thought from one element into another (form into meaning) the way a mechanical generator transforms the energy of mechanical motion into the energy of electricity. We can transform thought of the general into thought of the specific and back again.

And thought’s movement is imitated in a paragraph’s expressive structure. So writers should think of paragraphs as imitating cognitive motion – not something that is static and brittle. Thought moves and dances. Table 2 enumerates and depicts the motion of some generative opposites. Each generative opposite in Table 2 also represents a way of organizing a paragraph’s structure. The paragraph's structure/organization represents the movement of the writer’s thought.

For example, because the paragraph below begins with a definition followed by an example, it moves from general to specific, abstract to concrete, deductive to inductive, and genus to species. Writers, however, could choose to orient their thought in a different direction depending on their situation, purpose, and audience. This blog is structured deductively. That is, it moves from general principles to a specific example.

I begin by using the common place definition to write my definition of science fiction. Here is where writers can be creative. They select the concepts and parts they want to emphasize and that represent the reality they want to describe. Here is my definition:

The sentences in blue are the unique characteristics I chose to describe the part or elements that constitute the science fiction genre. The paragraph is not complete, however. Or, at least, the thought is not fully developed. I have to imagine my reader asking questions: “So, give me an example? What are specific instances of these features made present in a film? How do you support your claim?” (Notice the question / answer generative opposites are back in play and the claim/support generative opposites are in play). In general, all definitions are claims. I have to show that my definition is an accurate abstraction or generalization of reality. An example is the writer’s version of a scientist replicating a colleague’s experiment to confirm the alleged results. In this case, it is perception that is being replicated and confirmed.

Here is the answer to my reader’s question, the concrete and specific example (the text in black):

How Have We Gone from Blob to Form (List to Paragraph)?

Synthesis

Synthesis takes pride of place as a heuristic tool. After all, composition means “to put together” and synthesis means “to put together.” Essentially, I have used a paragraph to synthesize – juxtapose and order ideas to create a coherent meaning. I took the list of unorganized ideas and observations about science fiction and combined them using the common place (definition).

I also synthesized the ideas by giving them a shared cognitive trajectory, moving from general to specific, claim to support, abstract to concrete. To synthesize ideas writers make sure ideas are moving in the same direction. Readers psychologically feel the force of the generative opposites – the way we might feel the force of the tide on the beach. It is these cognitive movements (these changes or turns in thought) that determine when to begin a new paragraph. Writers lead the reader through the cognitive movements the way a dancer leads his partner through a series of moves. For example, the text in black (the example of a science fiction film) could be its own paragraph. It also works as part of a larger paragraph.

Sentences 1 to 3 are abstract and general. Sentences 4 to 12 provide a description of a specific example. I use the vocabulary of the definition’s unique characteristics (text in blue) to describe Blade Runner 2049 (text in black). This paragraph is a record of my cognitive movement from concepts to observations and back again. Moving from abstract to concrete placed an image in the readers’ minds – something they can grasp.

How Do You Move from Blob to Form?

We have observed the morphogenesis of a paragraph. The two blogs, so far, have provided one description of how writers generate ideas and then shape them into a paragraph using various heuristic tools. The questions remain: How do you employ these heuristic tools to compose your paragraphs, articles, and essays? How can you use the concepts to reflect on your own writing process that takes you from blob to form?

In Part 3, we will complete our observations and discussions regarding the heuristic tools that writers use to compose paragraphs. We will look closely at genre and reader expectations. And, one last time, we will discuss generative opposites and how to use them as tools for revision.

References

AFI. (2024). AFI’s 10 top 10: The greatest movies in 10 categories. American Film Institute. https://www.afi.com/afis-10-top-10/

Aldredge, J. (2022). A guide to the basic film genres (and how to use them). Premium Beat. https://www.premiumbeat.com/blog/guide-to-basic-film-genres/

MasterClass. (2022). How to identify film genres: Beginner’s guide to 13 film genres. https://www.masterclass.com/articles/how-to-identify-film-genres#13-classic-movie-genres

Quintilian. (c. 95 / 2002). The orator's education, volume II: books 3-5. Edited and translated by Donald A. Russell. Loeb Classical Library 125. Harvard University Press.