An Art of Choice: Form and Meaning

Series Title: Writing: An Art of Making Choices Blog #2

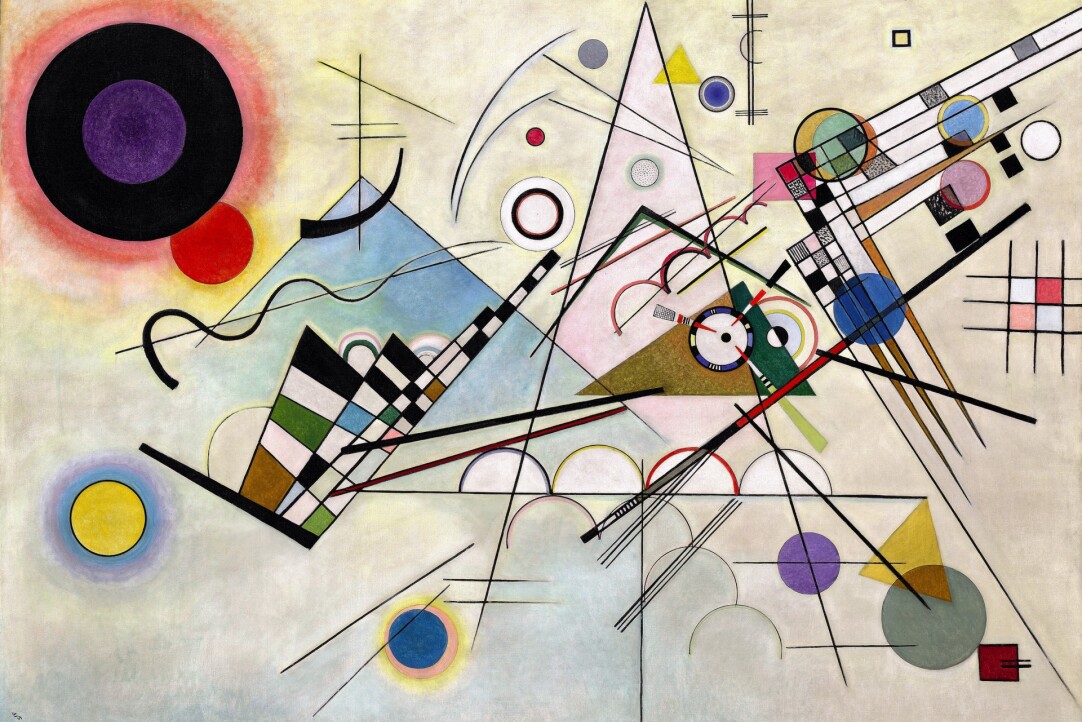

Vasily Kandinsky, Composition 8, July 1923, Guggenheim Museum, New York

By Dr. Melvin Hall,

Ph.D. in Composition and Rhetoric

from the University of Wisconsin — Madison.

First published on Medium, May 2023

We have to learn to write; but we’re born composers.

- Ann Berthoff, The Sense of Learning

Nature, creating its next leaf, does not look at the already created leaves, doesn’t look because it has in itself the whole form of the future leaf: it creates out of itself by an inner image and without a model. God created man in his own image and likeness without repeating himself.

Without Form, Is There Meaning?

The constellations in the night sky are a good example of what Berthoff means by “we’re born composers.” We give the cosmos’ indefinite expanse meaning by ordering the stars into definite expressive forms: Ursa Major and Orion chasing the Pleiades, for example. We are hardwired to seek order, arrangement, and form in our world. To compose means “to place together.” And by placing certain stars together, we compose the night sky and read our fate in the stellar forms we create. Similarly, a scientist composes her indefinite expanse of data when she shapes it into (or sees in it) recognizable patterns and constellations of meaning.

Image 1 Star map https://geo.koltyrin.ru/zvezdnaja_karta.php

We are more familiar thinking of Bach and Miles Davis as composers. Musicians arrange tone and rhythm to create musical forms (meanings). For example, out of a vast universe of tone and rhythm, Bach composed the tune Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring to give form (meaning) to his praise for his savior. And Miles Davis, when he composed So What, left a hint in the tune’s form why the composition was entitled “So What.” (Can the reader guess why Miles Davis named his piece “So What!”?)

Leitmotifs are very good examples of how musical form expresses meaning. When we hear this musical form (leitmotif), we know who is about to enter the scene and that we better run the other way. Or if we wanted to symbolically participate in a wild celebration of witches and demons without hazarding our life, we just have to listen to Mussorgsky’s Night on Bald Mountain.

The painter Vasily Kandinsky’s pictorial epigraph, Composition 8, illustrates the importance of form for the creation of meaning. For Kandinsky there are two elements that painters use to compose meaning: form and color. Kandinsky writes that form can by itself convey meaning, either abstract or objective. However, he states that “Colour cannot stand alone; it cannot dispense with boundaries of some kind. A never-ending extent of red can only be seen in the mind” (1914 / 1977, p. 28). In short, form gives color meaning because it sets limits or boundaries (triangle, square, circle, line, point). Without form’s definite boundaries color would be like the endless cosmos of stars — sublime, mystical, and ineffable. Likewise, without form’s discernable patterns, a scientist’s data would be an infinite sample of red without meaning.

What the above discussion boils down to for writers (especially academic writers) is this: to convey meaning, writers must give their thought form. They must compose themselves (their inner speech and thought, as Plato put it in the previous blog). And to compose their thought, they must analyze and imitate different types of linguistic forms that they encounter in the texts, articles, essays, and books they read.

Sky gazers compose by giving form to stars. Musicians compose by giving form to sound. Painters compose by giving form to color. And writers compose by giving form to language. For writers, composing is paradoxical because language is both the form and material of thought. For a painter like Kandinsky, the paradox of language (and meaning) is the equivalent of color being both the material and form of painting — as though red were its own form. So writers compose by giving structure to language. And, in giving structure to language, writers form their thought, both in their minds and hopefully their readers’ minds. To convey meaning simply means to transfer form from one mind to another.

How Do Writers Learn to Compose Language and Thought?

Writers learn to compose by analyzing, imitating, and varying language forms. Scholars have been observing the forms of language and thought for quite some time. And we can benefit from their classification of linguistic forms for the invention and arrangement of our thought. A writer’s linguistic material and form can be classified into five general categories. The two-column table below is a working list of the different linguistic forms. Prior to reading the table, however, first observe how the orders of form work in the composition of a single paragraph.

How Can the Orders of Form Be Used to Analyze the Composition of Paragraph?

I have chosen the paragraph for analysis because it demonstrates how the author, Lewis Thomas, amalgamates a variety of linguistic forms to create a unified (unity is the development of a single idea in a paragraph) and coherent (coherence is the conceptual and logical order linking the parts of a paragraph into a harmonious whole) paragraph. Unity and coherence are considered the primary organizational principles of a well-composed paragraph.

The paragraph for analysis is written by the American biologist and scientist Lewis Thomas. It is the second paragraph of an eleven-paragraph essay entitled “Social Talk.” The essay was first published in the New England Journal of Medicine in the early 1970’s.

In his essay, Thomas is trying to convey the paradox or difficulty of classifying humans as a social and/or independent animal. Let us observe how Thomas uses different linguistic forms in a single paragraph to compose his thought and convey his idea to his reader. While doing so, we will learn different linguistic forms that we can use to hone our own writing skills. In the end, the most important skill is that of being a close reader of linguistic forms/styles so that each writer can observe them, learn them, and imitate them, in her own writing.

Parts of Speech and Sentence Patterns (1st and 2nd Orders of Form)

The first form we notice is the repetition of the compound-complex sentence pattern (Cp-Cx). Of the six sentences, five are Cp-Cx and one is Cp.

The first orders of linguistic form that a writer must be proficient with are parts of speech and sentence structures. We analyzed the first sentence for its structure. Can you analyze the remaining five sentences, identifying the parts of speech (subject, verb, coordinator, and subordinator), clauses (independent and dependent), and sentence types?

Syntax — Location of Subject and Verb (First Order of Form)

It is a guideline that clear English prose requires subjects to be placed at the beginning of sentences next to or as close as possible to the verb. Here we notice that Thomas begins every independent and dependent clause with the subject followed by the verb. In the example paragraph, all the subjects are bold type and underlined. The verbs are bold without an underline. Again, sentence one serves as an example.

Rhetorical and Linguistic Schemes (Third Order of Form)

NB: Scheme is another word for form.

1. Parallelism — similarity of structure in a pair or series of related words, phrases, or clauses

Thomas masterfully uses parallel structures at a variety of linguistic levels. For example, in paragraph 1, sentence 4 of his essay we find this sentence:

We clearly notice Thomas’ use of parallelism in a single sentence. Lewis repeats the same verbal structure (simple perfect) in each phrase. Doing so allows him to economically describe the complex behavior of social species in just a few words and phrases.

The sample paragraph’s, macro-structure is based on parallelism. Each sentence (but one) follows the same Cp-Cx structure (and as we will see below there are two specific types of parallelism made present in Thomas’ paragraph: anaphora and antithesis). Sentence three also contains a brief use of parallelism. Note the use of two successive gerund verbal phrases marked in green (see the paragraph above).

2. Anaphora — repetition of the same word or group of words at the beginnings of successive clauses

Anaphora is quite easy to spot in Lewis’ paragraph. Nearly each clause begins with “we.” Notice all the bold type and underlined “we’s” in the paragraph.

3. Parenthesis — insertion of some verbal unit in a position that interrupts the normal syntactical flow of the sentence

Thomas’ use of parenthesis is also easy to identify. In sentence five, he interrupts the flow of his thought with an aside clearly marked by open and closed parentheses, colored orange below. In sentence two, the parenthetical aside is more difficult to identify because it is placed between commas, also colored in orange below.

4. Antithesis — the juxtaposition of contrasting ideas, often in parallel structure

Thomas makes evident use of antithesis to shape his thought. Each sentence presents contrasting ideas indicated by the repeated use of coordinators that mark contrast (yet and but).

Rhetorical Common Places/Forms (Third and Forth Orders of Form)

We can add the rhetorical common place comparison (specifically both similarity and difference) to the list of linguistic and rhetorical forms Thomas uses to give shape to his thought. In this case, he outlines some human characteristics that are similar to social animals. In keeping with his scheme of antithesis, he then outlines some human characteristics that are different from social animals.

Why Is Writing So Complex?

What makes Thomas’ paragraph exemplary is the command he demonstrates over various levels of linguistic form (from parts of speech to the paragraph’s unity and coherence). A writer, like Thomas, must not only learn but internalize each level of linguistic form. However, each level of linguistic organization has its own set of principles and rules for achieving its ideal form. In other words, if a writer learns the rules and patterns for drafting excellent sentences, these rules and patterns are necessary but not sufficient for composing paragraphs.

Put another way: An isolated sentence is a complete form and can be governed by its own principles of organization. However, from the perspective of a paragraph, the sentence becomes a particular part of a larger whole, and it now must be governed by the organizing principles of a higher order (the paragraph) as well as its own internal principles of form. It is a writer’s aim to bring these different levels of form (which often conflict) into harmony.

Writing is complex because a writer is trying to harmonize many different levels of organizing principles, from parts of speech to a whole composition:

1. Words (parts of speech and vocabulary/diction)

2. Clauses and sentences

3. Rhetorical Common Places and Schemes

4. Paragraphs

5. Genre (article and essay types)

Thomas, in a single paragraph shows how a writer composes meaning by mastering the orders of linguistic form and making them conform to a paragraph’s higher order organizational principles (unity and coherence). The next step would be to read the entire essay and analyze how paragraph #2 fits within the larger whole and conforms to the higher-level organizational principles of the genre.

Form and the Art of Choice

Writers become composers when they have internalized the organizing principles of each level of form and can bring them into harmony. In turn, the different levels and styles of form are tools that a writer uses to help her make choices as she composes her thought.

In this blog, writers have learned the following:

1. Form is meaning and learning.

2. Writers must be close readers and analyzers of form in written essays (as we closely read Thomas’ paragraph for form).

3. Form has five levels of organizing principles that a writer must harmonize.

4. Stylistic and organizational forms are the tools of writer’s art of choice.

5. We are all born composers, looking for the patterns and forms that give our lives meaning.

Let’s say a writer has learned and internalized all the levels of form, from parts of speech to genre. This will be necessary but still not sufficient for composing articles and essays. Perhaps the highest level of organizing principle a writer needs to practice is the “process” of composing, harmonizing the levels of form into a coherent article or essay. And the composing process is the topic of our next blog.

References

Corbett, P.J., & Connors, R.J. (1999). Classical rhetoric for the modern student. Oxford University Press.

Kandinsky, V. (1914 / 1977). Concerning the spiritual in art. (M.T.H. Sadler, Tans.). Dover Publications, Inc.

Kinneavy, J. (1997). “The basic aims of discourse.” In Cross-talk in comp theory: A reader. Ed. Victor Villanueva, Jr. National Council of Teachers of English.

Thomas, L. (1974). “Social talk.” In The lives of a cell: Notes of a biology watcher. (pp. 84–88). Penguin.