Plato, Rhetorical Art, ChatGPT, and The Sophist in the Machine

Series Title: Writing: An Art of Making Choices Blog#1

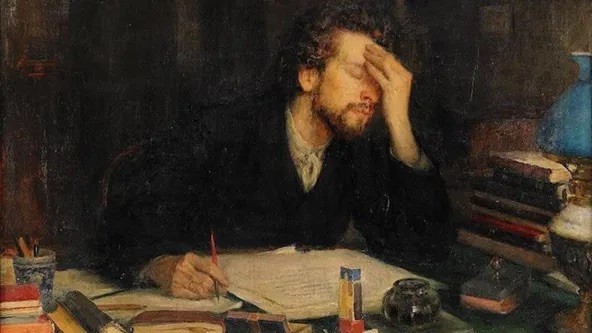

Leonid Pasternak, “The Throes of Creativity” Муки творчества. Автор: Л.О. Пастернак.

By Dr. Melvin Hall,

Ph.D. in Composition and Rhetoric

from the University of Wisconsin — Madison.

First published on Medium, April 2023

❞ The Phaedrus reminds us that all writing is merely a “reminder”: the real activity of teaching and learning goes on not on the page but in the souls of people.

- Martha Nussbaum, “This Story Isn’t True: Madness, Reason, and Recantation in the Phaedrus”

❞ He who familiarizes himself with the old and thereby understands the new is fit to be a teacher.

- Lun Yu (Qtd. in Hu, S. The Development of the Logical Method in China).

Introduction

In this blog’s visual epigraph, Leonid Pasternak depicts a writer seemingly caught in a rhetorical situation — the creative and awful moment of choice. All we know is that he has made the initial choice to sit at his desk and to begin or resume the writing process. We can only imagine what choices he is making and where he might be in his writing process. The technology surrounding Pasternak’s writer is old fashioned: print books, nib pens, inkwell, paper, wooden block stamp, and desk lamp with which to burn the midnight oil.

However, the creative struggle, the working through of the writing process, depicted in the writer’s posture and facial expression is contemporaneous. Although our writing instruments have changed, we easily identify with the writer’s pain (or passion) of creative choice.

This blog is the first in a series that explores the relationship between the writing process, critical thinking, and form as heuristic devices for helping writers make choices. As I contemplated each practical, skill-oriented topic, I asked: Whether we study the writing process, critical thinking, form, style, grammar, syntax, genre, revision, thesis statements, citations, argument, persuasion, what skill or concept is always being taught? Choice[1] is the culminating skill and unifying concept made present in every writing center and classroom. Put another way, each writing lesson is an individuation of a general writing course teaching the use of tools and methods for passively or actively making choices.

Our current writing environment is dominated by what Burke (1944 / 1984) calls a “technological psychosis” (p. 44). By “psychosis” Burke means the predominate economic modes and patterns of production that shape our modes and patterns of thought, choice, and action (Burke, 1944 / 1984, pp. 37–40). This is another way of saying a writer’s environment (technological habits) makes her choices for her. Current developments in our writing environment (our technological modes of production) bring into sharp relief the pride of place the art of choice occupies among writing skills and styles. The advent of AI labor saving devices like ChatGPT and Caktus AI have altered the writer’s means of production so that machines do not assist or shape a writer’s choices; they make the choices. Does ChatGPT experience the “throes of creativity” the way Pasternak’s writer does? Or do ChatGPT’s writing choices shape its soul the way Plato and Nussbaum in this blog’s epigraph suggest Pasternak’s writer is shaping his soul when he writes?

In keeping with Lun Yu’s advice, if we familiarize ourselves with the old — in this case rhetoric, we will understand our new writing situation and begin to answer the above questions. To acquaint ourselves with the old, we will read Plato’s analysis of the rhetorical art of choice in his dialogue, Gorgias. Doing so will help us lay the theoretical and conceptual groundwork for future blogs in the series “Writing: An Art of Making Choices.” After all, rhetoric, from one point of view, is a technical system of communication developed over two-thousand years (from ancient Athens to modern Moscow) to assist humans in making eloquent choices.

[1] Phronēsis — practical reason and judgment

What is Meant by Rhetorical?

By making choices, writers shape their thought, giving it cognitive and expressive form. We call a writer’s situation “rhetorical” because she is confronted with a complex of contingent choices. Simply put, a situation is rhetorical when circumstances compel a writer, leader, orator, or everyman to consciously select and decide both what to say and how to say it.

What Does Plato Mean by Rhetorical Art?

Writing centers, teachers, and students assume that writing can be taught. In other words, we assume that there is an art of choice that can help a writer select the best tools, words, genre, organization, and style to successfully communicate her meaning to her readers in any particular situation. More importantly, we assume that by following a series of steps (the writing process) or by imitating conventions of form (an academic genre’s constituent parts) a writer will be successful — that is published. But is there such an art that guarantees writing success?

Plato’s Answer

Socrates puts the question to the sophists: “Should we assert that you [Gorgias] are able to make others rhetoricians [writers] too?” (Plato, ca. 385 B.C.E. /1998, 449b). Gorgias claims that he is a craftsman of persuasive speech in legislative assemblies and law courts. He claims further that he can teach his students to not only be successful in composing speeches but that he can teach his students to choose between the just and the unjust, making his students and the Athenian audience ethically and morally better through speech (Plato, ca. 385 B.C.E. /1998, 449b; 456a–457c; 460a–b).

Socrates, however, sets a very high standard for Gorgias to warrant inclusion in the guild of craftsmen and teachers of discursive justice. He claims that Gorgias is not a craftsman but the opposite — a sophist. He depends on chance, luck, trial and error (experience), cookery, cosmetics (flattery) and guessing to compose successful speeches (Plato, ca. 385 B.C.E. /1998, 463a–b; 465a–466a; 500e–501c). A true craftsman and teacher, on the other hand, follows a “reasoned account,” a clear methodology, and step by step process, demonstrating an understanding of the causes of what she aims to produce (Plato, ca. 385 B.C.E. /1998, 465a & 501a). An art of choice, then, is a reasoned account of the method one can use to create a desired outcome or form.

Socrates, arguably, makes a far more important observation. He links the art (the reasoned account) of producing speeches (writing) to the art of producing well formed, beautiful, and just souls. In short, as Nussbaum (2001) avers, to shape written discourse is to order the soul of the writer (p. 224). The Stranger in Plato’s Sophist (ca. 390 B.C.E. / 1921) states the case this way: “. . . thought and speech are the same; only the former, which is a silent inner conversation of the soul with itself [emphasis added], has been given the special name of thought” (263e). This means that Pasternak is not simply depicting an author arranging words and paragraphs on paper, written speech. He makes visible a man ordering his soul.

So, for Socrates, what is important is writing’s artful power to produce not simply discourse (conveyance of information, machines do this) but well-shaped souls. And Socrates applies the same definition of an art of discourse (an ordered, reasoned account) to that of an ideal soul. He states: “Well then, won’t the good man, who speaks with a view to the best, say what he says not at random but looking off toward something? [emphasis added]. Just as all the other craftsmen look toward their work when each chooses and applies what he applies, not at random, but in order that he can get this thing he is working on to have a certain form [emphasis added]” (503e). Socrates goes on to enumerate different craftsmen “painters, house builders, shipwrights” as “compel[ing] one thing to fit and harmonize with another, until he has composed the whole as an arranged and ordered thing” (Plato, ca. 385 B.C.E. /1998, 504a).

The writer (rhetor) and teacher of writing, then, are aiming not simply at ordering a spoken or written discourse into a coherent form, but are aiming at ordering and harmonizing the soul itself. “Now, the virtue of each thing — of implement, body, soul too, and every living being — does not come to be present in the finest manner simply at random, but by arrangement, correctness, and art, which has been assigned to each of them. . .,” Socrates avows (Plato, ca. 385 B.C.E. /1998, 506d). And because speech and thought (the silent inner speech of the soul) are in essence one and the same, the virtue of writing (an art of choice) is that it shapes the soul by “arrangement, correctness, and art.”

Finally, what is Plato’s answer to our question: Is there an art of choice or an art that guarantees writing success? For Plato rhetoric has the potential to be a science of choice (practical reason) that produces well-ordered, just, moderate, and beautiful forms of speech as well as just and beautiful souls in both the writer and reader. This is perhaps one reason why Nietzsche (ca. 1874 / 1983) stated that rhetoric for the ancient Greeks was “the highest spiritual activity of the well-educated political man” (p. 96). But whether or not this art works as efficiently as the cobbler’s, shipwright’s, or house builder’s art (churning out the same successful written product each time) is the topic for our next two blogs when we discuss form.

Our Writing Situation Now — The Sophist in the Machine

A good way to summarize what we have learned from Plato is to apply his theory to our current writing situation, the advent of ChatGPT. Writers and speakers attempt to apply an ordered and reasoned art of choice to shape both their discourse and their soul for the better. It is the act of choice that orders discourse and soul. When one uses ChatGPT, the creative act of choice is located with the machine. And it raises the question: if the machine makes the choices, is the machine shaping our souls as well as our discourse? If so, this means that AI is the sophist in the machine. As Socrates might put it: AI flatters us by making us think that we make the choices; it flatters our interests and desire to succeed by catering to our commands and pleasures; it flatters us by creating the illusion that it is a kindred soul producing the silent inner conversation (thought) of our soul. Like a sophist exciting the Athenian hoi polloi, the machine gives us what we want and tells us what we want to hear.

Conclusion

As I stated in the beginning, this blog is the first in a series of blogs that explore the relationship between the writing process, critical thinking, form and technology as heuristic devices for helping writers make choices. I assume, like Socrates and Plato, that there is an art of writing — a reasoned and systematic method for helping writers invent ideas and make choices. The forthcoming blogs will explore specifically how the writing process, form, and critical thinking provide that reasoned and systematic method. In addition, we will look closely at strategies for making choices to shape paragraphs, analyze sentence style, synthesize information, and write definitions.

Finally, I believe that Socrates has trenchantly described an important purpose of writing centers, classroom workshops, and one-on-one consultations. He noted that a craftsman “look[s] off toward something” in order to “get this thing he is working on to have a certain form” (Plato, ca. 385 B.C.E. /1998, 503e). Is this not what we do in writing centers and classrooms? We help each other to see the thing we aspire to create; and then we help each other to make the choices to get this thing (our article and soul) to have a certain form — the topic for our second blog in the series “Writing: An Art of Making Choices.”

References

Burke, K. (1984). Permanence and change: An anatomy of purpose. (3rd ed.). University of California Press. (Original work published 1944)

Nietzsche, F., & Blair, C. (ca. 1874 / 1983). Nietzsche’s lecture notes on rhetoric: A translation. Philosophy & Rhetoric, (16) 2, pp. 94–129. (Original work published ca. 1874)

Nussbaum, M.C. (2001). The fragility of goodness: Luck and ethics in Greek tragedy and philosophy. (Revised Edition). Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1986)

Plato. (ca. 385 BCE / 1998). Gorgias. (J. H. Nichols Jr., Trans.) Cornell University Press. (Original work published ca. 385–387 BCE)

Plato. (ca. 390 BCE / 1921). Theaetetus. Sophist. (H. N. Fowler, Trans.). Loeb Classical Library 123. Harvard University Press. DOI: 10.4159/DLCL.plato_philosopher-sophist.1921 (Original work published ca. 390 BCE)

Hu, S. (1922). The development of the logical method in ancient China. Shanghai Oriental Book Co.