An Art of Choice: Style and Sentences (Part 3)

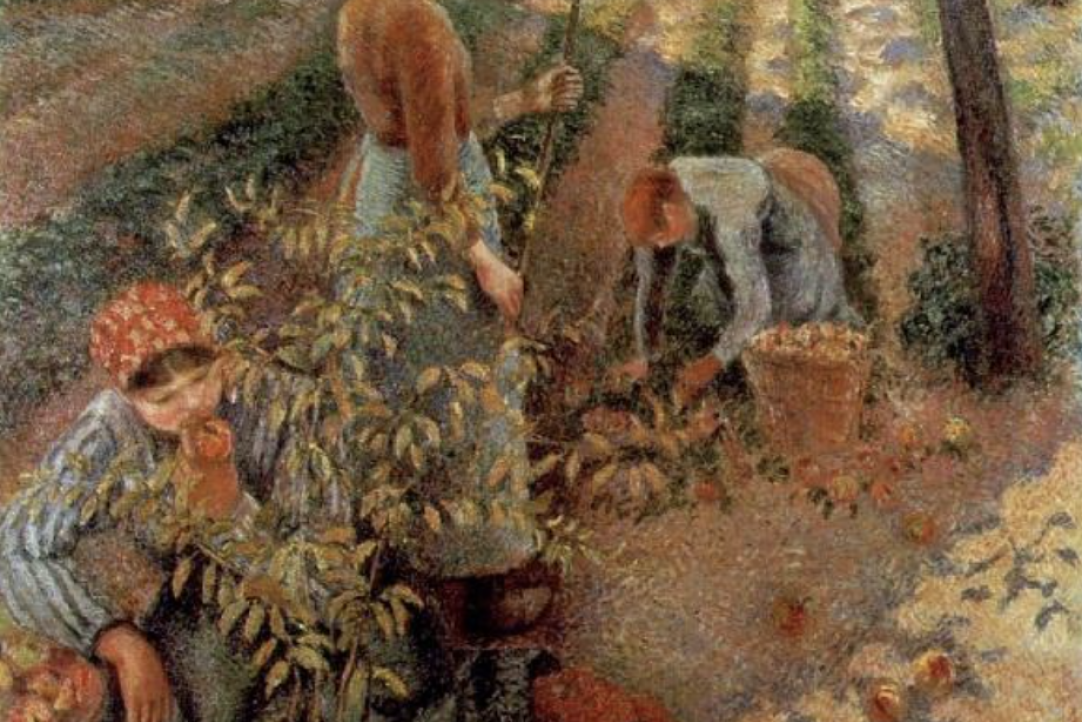

Camille Pissarro, The Apple Pickers, Oil on canvas, 1886, Wikiart

By Dr. Melvin Hall,

Ph.D. in Composition and Rhetoric

from the University of Wisconsin — Madison.

And, in impressing herself thus upon those about her, it seemed that [the Duchess] tempered us all to her own quality and fashion, wherefore each one strove to imitate her style, deriving, as it were, a rule of fine manners from the presence of so great and virtuous a lady.

- Castiglione, The Book of the Courtier

It seems to me, therefore, that anyone who wishes to avoid all doubt and feel quite sure must set himself to imitating someone who by common consent is acknowledged to be good. . . . But we are today so forward that we do not stoop to do what the good writers of old did, namely, to practice imitation, without which I deem it impossible to write well.

- Messer Frederico in The Book of the Courtier by Castiglione

Do Scientists and Scholars, Like Artists, Imitate Style?

By 1882, George Seurat had fully dedicated himself to “scientific-impressionism,” exclusively using the technique of tiny brush strokes (dots) of primary color to compose his paintings. Paul Signac and Camille Pissarro, his fellow French artists, joined him. All three, from 1884 to the Eighth Exhibition of the Impressionists in 1886, assiduously imitated the new pointillist style in their compositions. (Rewald, 1990, pp. 12, 27, and 98)

A curious thing happened at the exhibition. The three painters’ compositions were displayed in the same room. The public could not identify the works of Seurat (A Sunday on La Grande Jatte), Signac (The Milliners), and Pissarro (Apple-Picking). Although the artists’ signatures were on their paintings, it appeared that the same painter had composed them all. The public and experienced art critics alike thought the exhibit organizers were playing a joke; or worse, the exhibition was a sham. So carefully had the three artists imitated the pointillist style that George Moore, an art critic very familiar with Pissarro’s style, had to get on his knees and closely scrutinize Pissarro’s tiny dots before he could recognize an iota of idiosyncrasy (Rewald, 1990, pp. 98-103).

The three artists fixated on method (style); method is the artists’ subject. The artists want viewers to see primarily the method work and secondarily the depicted scenes and people. Seurat stated bluntly that viewers “see poetry in what I have done. No, I apply my method and that is all there is to it” (as cited in Rewald, 1990, p. 95). He went on to add that subject is a trivial matter. In other words, the method can be applied to any subject with scientific (and artistic) rigor to reproduce the same result, like a scientist replicating colleagues’ experiments.

Scientists, like artists, are obsessed with method (style and form). By adhering to their scientific paradigms, they confidently perceive and describe nature. Scientists, too, make commitments to their field’s interpretive and methodological instruments. One of these instruments is writing style. And, like the pointillist painters, scientists closely imitate their discipline’s writing styles. So closely, in fact, it is difficult at times to distinguish individual authorship. In short, one becomes a scientist by adopting and imitating the group’s stereotyped writing style, like a courtier imitating the court’s style.

Readers of the journal Science, for example, might feel like Parisians at the 1886 Exhibition of Impressionists, perplexed as they move from one article to the next, unable to distinguish one author from another. The articles in Science so carefully follow a stereotyped style (sentence choice, sentence arrangement, and clause patterns) it appears as though the same author may have written them all (The editors, of course, exert their shaping force). Unlike the Parisians of 1886, however, we don’t think this stereotyped style is an attempt to pull the wool over our eyes. We accept the imitated, recursive, and unvaried writing style as the standard of scientific truth and objective validity. The more standardized the style the more certain and confident we are in the reported claims and support. At least, by imitating this stereotyped style, scientists hope to transmit to the reader the intended rhetorical and emotional effect of accuracy, certainty, validity, and confidence.

In Part 1, using a color-code, we identified the types of sentences that Cooks and Holden use in their article (Image 1). Now, we will use that data to analyze Cooks and Holden’s style. We will alternate between looking at the grammatical types of sentences (a writer’s brush strokes of thought) and through the grammar to the authors’ arrangement of those sentences to create their telegraphic style.

I label the stereotyped writing style published in Science telegraphic minimalism. It contrasts with Lewis Thomas’ baroque counterpoint discussed in Part 2. The scientific article we analyze below, “Breaking Down Microdroplet Chemistry” by R. Graham Cooks and Dylan Holden, embodies the predominant style used throughout the journal Science.

What Are the Attributes of Cooks and Holden’s Writing Style?

First, we will look at the authors’ grammar – use of phrases, clauses, and types of sentences. These structures can’t be altered; they must follow the grammatical principles of word order dictated by the lower-level forms’ grammatical rules.

Phrases: Phrases follow ordinary and simple use. For example, the longest simple sentence (38 words) is the only case where the writers repeat parallel (verbal) phrases in a series (See Sample 1). The prepositional phrase is the most common phrase used. Prepositional phrases are also used as ordinary adjectives or adverbs qualifying or modify a subject or verb (See the first example in Sample 2). Only five times are prepositional phrases used as an introductory phrase to the sentence’s main clause (See the second example in Sample 2 for one instance and Sample 5 for the remaining instances).

Style, Arrangement (Higher-Level Forms)

Cooks and Harden’s arrangement and order of the grammatical forms imposes boundary conditions on those lower-order forms to produce their telegraphic minimalist style.

The first boundary condition we notice is Cooks and Harden’s choice to use only simple and complex sentences, no compound nor compound-complex sentences. And, importantly, 55% of the sentences are simple sentences characterized by their brevity.

The second boundary condition is that the authors begin all but ten sentences with a subject. Sample 4 shows the repetition of a subject used to begin each sentence of paragraph 6. This pattern of beginning a sentence with a subject is repeated throughout the article. Sample 5 shows that only 10 sentences of 44 begin with opening phrases or words rather than a subject. The lack of opening phrases contributes to the authors’ telegraphic minimalism. The stereotyped repetition of the same concise forms is the style’s key attribute. Even the authors’ complex sentences follow a concise, stereotyped pattern.

The third boundary condition, then, is the repeated pattern of complex sentences. Sample 6 illustrates a typical complex sentence pattern repeated throughout the article. There is no deviation in the structure of the complex sentences. Sample 3 above shows the stereotyped pattern of all 20 complex sentences in the article. It is a remarkable stereotyped pattern repeated at the scale of the article and in paragraph 5 where the paragraph’s six sentences imitate the same concise complex sentence pattern without deviation (See Sample 3, paragraph 5 sentences).

The authors’ fourth boundary condition is the repetition of the concise sentence structures (simple and complex) throughout the article. This repetition of concise form is represented in the sequence of sentences depicted in Table 2. We note the predominate occurrence of simple sentences. And the repetition of the same complex sentence pattern in paragraph five. Table 2 also depicts a near isomorphic repetition of paragraph length (five to seven sentences in each paragraph).

What Is the Key Advice for Novice and Experienced Writers Looking for a Model of Style?

Cooks and Holden’s article provides a good model for writing scientific and scholarly articles. The following list summarizes Cooks and Holden’s style and provides general guidelines for writers looking for a model to imitate and practice.

-

Use a majority of simple sentences (55% in Cooks and Holden’s article are simple sentences; but remember that simple sentence does not always mean “short.” Cooks and Holden’s longest simple sentence is 38 words)

-

Begin sentences with clear subjects near the main verb (77% of Cooks and Holden’s sentences begin with subjects – without introductory phrases. See Sample 4 above.)

-

Limit severely the use of compound and compound-complex sentences (0% of Cooks and Holden’s sentences are compound or compound-complex)

-

Repeat concise sentence patterns – such as complex sentences with simple subordinate clause patterns (Nearly all 20 of Cooks and Holden’s complex sentences repeat the same pattern, see Sample 3 above)

-

Repeat sentence patterns without or with very little variety throughout the entire article. (Cooks and Holden rarely deviate from established sentence patterns)

-

It is a virtue to repeat sentence forms and patterns.

In general, all of the articles published in the journal Science follow the same six guidelines listed above. Curiously, most writing instructors and textbooks discourage repetition in student writing. But what we have learned from closely reading Thomas’ essay in Part 2 and Cooks and Holden’s article here in Part 3 is that imitation and repetition of form is what creates writers’ styles. What differentiates their styles is what pattern and forms the authors choose to imitate and repeat.

What Have We Considered in This Blog’s Three Parts?

In this blog’s three parts (Part 1), (Part 2), I performed a dissection of two writers’ written styles while readers looked on, making their own observations. From the demonstration, readers will take away their own insights, principles, and practices about the imitation of style.

Here is a summary of the main elements of style we considered throughout the blog’s three parts:

We considered that style is the imitation and repetition of form. We observed Thomas repeat compound and parallel structures in catenated series to create his baroque counterpoint style used to compose a reflective, formal essay. Thomas writing style strive to achieve a Bach counterpoint. We observed Cooks and Holden imitate and repeat the same concise structures of simple and complex sentences to create their telegraphic minimalist style to compose a standardized, scientific article. We can see that the authors’ writing style aspires to achieve the limpid, reassuring minimalism of a Philip Glass composition (Opening). Summary 1 juxtaposes the two different writing styles that we began with in Part 1.

We considered that style is a hierarchy of forms – lower-order grammar (phrase and clause) shaped and constrained by the boundary conditions of higher-order forms (sentence arrangement and order).

Most importantly, I believe, we have begun to contemplate the simple habit of noticing style, not taking it for granted or overlooking it. Only by disciplined study of style, by noticing, can writers develop their own repertoire of techniques and command style’s forms. It is this attitude of wonder, appreciation, and delight in creative and expressive forms of many kinds (nature, art, science, music – the world of forms around us) that we need to imitate most of all. Practicing the habit of noticing form is how we mature from quasi-scholars to writer-scholars.

Finally, if style is the imitation and repetition of form, perhaps the most important choice a writer makes is what styles to notice, study, and imitate. The life of a writer’s mind, after all, is influenced and shaped by what he or she reads and hears.

Table 1 and Table 2

References

Cooks, R.G., & Holden, D.T. (2024). Breaking down microdroplet chemistry. Science, 384(6699), 958-959.

Rewald, J. (1990). Seurat: A biography. Harry N. Abrams, Inc.