An Art of Choice: Composing Paragraphs (Part 1)

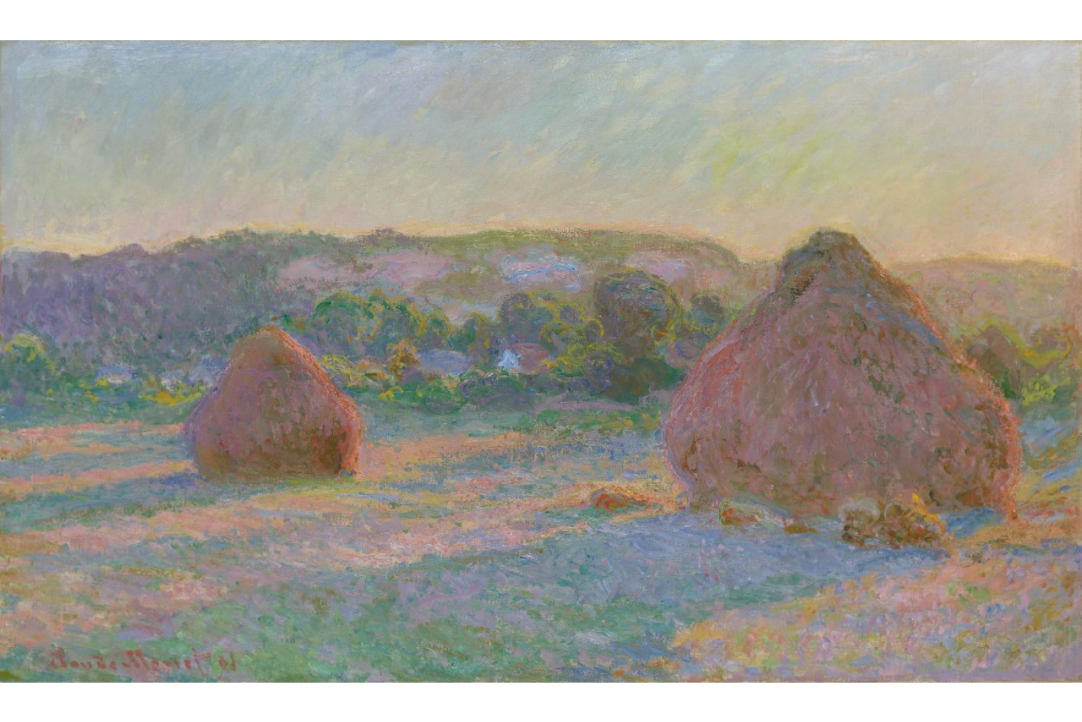

Claude Monet, Stack of Wheat, (Thaw, Sunset), Oil on Canvas, 1891, Art Institute of Chicago

By Dr. Melvin Hall,

Ph.D. in Composition and Rhetoric

from the University of Wisconsin — Madison.

❞ I thought and pondered – vainly. I felt that blank incapability of invention which is the greatest misery of authorship, when dull Nothing replies to our anxious invocations. Have you thought of a story? I was asked each morning, and each morning I was forced to reply with a mortifying negative.

❞ Invention, it must be humbly admitted, does not consist in creating out of void, but out of chaos; the materials must, in the first place, be afforded: It can give form to dark, shapeless substances, but cannot bring into being the substance itself. . . . Invention consists in the capacity of seizing on the capabilities of a subject, and in the power of moulding and fashioning ideas suggested to it.

Why Is a Paragraph a Strange Tool?

What Are Our Goals?

Our first goal is to describe a paragraph’s morphogenesis – the process by which its form and thought simultaneously coalesce into a coherent meaning. We will follow the stages of a paragraph’s development from nothing to a complete thought.

Our second goal is to suggest heuristic tools that writers can use to draft paragraphs and organize their thought.

-

Affording: Discovering Ideas (Part #1)

-

Drafting: Composing and Forming Thought (Part #2)

-

Revising: Re-organizing and Re-forming Thought (Part #3)

To emphasize terms and concepts that deserve deeper contemplation and continued exploration, I use bold and underline.

What Are Heuristic Tools?

A heuristic tool is a linguistic or cognitive form a writer uses to invent, discover, and organize thought.

We can classify heuristic tools into five types (or domains):

1. generative opposites

2. common places (topoi)

3. synthesis

4. intended meaning

5. genre and audience

Generative opposites (sometimes called antinomies) are especially powerful tools for creating ideas. Throughout the blog, I will highlight when these tools are active. We will discuss common places and synthesis in Part #2.

The last two heuristic tools shape a writer’s thought and writing style (a paragraph’s typography and size). We will discuss these in Part #3.

What Does a Paragraph’s Morphogenesis Begin With?

Writing, like thinking, usually begins with a question. Notice that question/answer is one of the generative opposites. Questions give writers a desire to write, an impulse to respond. A question will:

-

limit the writing process’ scope and focus the writer’s attention on a manageable topic

-

generate language through the back-and-forth of question and answer

-

turn writing into a conversation between writer and reader

Here is a research question or research problem: How have science fiction films evolved since 1960?

We can imagine a film scholar writing an article that will answer this question. In general, when you have a writing prompt, research question, or research objective, break them down into their key terms/concepts and ask questions about those key terms/concepts:

What is a science fiction film? Or what is the science fiction film genre? Who makes science fiction films? Who watches science fiction films?

When do science fiction films take place? When were science fiction films first made? Why are science fiction films made? Why do we watch science fiction films?

How are science fiction films made?

Where do science fiction films take place?

I choose to answer: What is the science fiction film genre? The other questions, I will keep in mind, because they will help me generate ideas as I learn about the science fiction film genre. In any case, the film scholar will have to answer this basic question of definition in her 20- to 30-page article answering the larger question about the evolution of science fiction.

Now that we have a question, we need to answer it. To answer our research question, we will write a paragraph. First, however, we need material to shape into a paragraph.

How Do We Generate Ideas?

Mary Shelley, in this blog’s epigraphs, describes a writer’s need for inchoate material. It is impossible for writers to generate ideas or form paragraphs from nothing. Writers need to be “afforded” a jumble of ideas (Shelly calls it chaos).

Ideas are afforded through dialogue, reading, and observation (there really is no other way). The first thing I will do, then, is start reading and observing, using my question (what is a science fiction film?) to focus my close reading and observations. As I read and observe, the generative opposites will play a very important part in helping me generate ideas (even when I am not aware that I am using the generative opposites).

Read

I will read articles to learn how other writers have described the science fiction genre. I will take notes – not necessarily too organized (chaos at this stage is good). I will look for similarities and differences between the articles’ descriptions of science fiction. In addition, I will read analytically, dividing science fiction into its elemental parts. Note the synthesis / analysis and word / thought generative opposites are operational when doing research.

I am analyzing science fiction, dividing it into its parts and looking for words and concepts. I am generating the vocabulary of ideas and conceptual framework that will help me discover science fiction’s identifiable parts. Without the words and concepts, I can’t describe what I am observing (perception / conception).

Observe

To observe, I will watch science fiction films (2001 a Space Odyssey, Blade Runner 2049). Observation is part of the generative opposites perception / conception. I write notes about the attributes I notice that make these films “science fiction.” I compare my observations with those made by the writers in the articles I read. My perceptions (or observations) will become concepts (words and thoughts) that I can use to help me describe science fiction.

What Is Affordance?

Marry Shelly, in her 1831 introduction to Frankenstein, describes how she was afforded the idea that became her novel in conversation with her husband Percy and friend Lord Byron: a question was posed. To be afforded, according to Merriam-Webster, suggests to be given or provided something. It also suggests that something is made “naturally available,” like the sun affords warmth. Conversation, reading, dialogue, observation, and writing naturally make available ideas we use to shape our thought. Writers are needy. We depend on our environment and interaction with others to generate ideas. Now, AI, too, affords us with ideas and material.

I read three on-line articles about film genre. I documented the descriptive terms used by the authors to describe science fiction. In essence, while I was reading the articles and watching the films, I took science fiction apart (analysis). I then wrote a list based on the observations I made when watching science fiction films (synthesis). What I perceived (or noticed) in the films became concepts, words, and thoughts in my list. The list is important chaos; it is the affordance of ideas with which I can now work. I will take these ideas and shape them into a paragraph in Part #2.

How Are You Afforded the Ideas and Material You Use to Write?

Scientists and scholars, no matter how advanced or experienced, use the generative process we just described. We slowed the thinking process down (the list) so that we could better observe it. Each writer has their own process of affordance: relies on different sources (books, films, colleagues, experiments, research, theories), goes at different speeds (simply begins to write or engages in lengthy reading, observation, and note taking), and emphasizes different generative opposites. Where do your ideas come from?

References

AFI. (2024). AFI’s 10 top 10: The greatest movies in 10 categories. American Film Institute. https://www.afi.com/afis-10-top-10/

Aldredge, J. (2022). A guide to the basic film genres (and how to use them). Premium Beat. https://www.premiumbeat.com/blog/guide-to-basic-film-genres/

MasterClass. (2022). How to identify film genres: Beginner’s guide to 13 film genres. https://www.masterclass.com/articles/how-to-identify-film-genres#13-classic-movie-genres

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Afford. In Merriam Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved January 30, 2024, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/afford

Shelly, M. (1831 / 2018). Introduction to Frankenstein, third edition (1831). In Frankenstein (pp. 237 - 241). Penguin Books.